Exploring the Bittersweet Legacy Queer R&B Artists Leave Behind

Can we talk about this?

Whether you're 42, 24, or somewhere in between, I'm sure you've been on a club or party dancefloor with icy blue lighting while the 1993 Babyface-penned Tevin Campbell hit "Can We Talk" marinates the function. Arguably, the song evolved past hit status—liquifying itself, becoming part of our misty cultural atmosphere.

Call me crazy, but I found out that Tevin Campbell was gay through a TikTok comment section. Perhaps similar to many others who fell across the news during their daily scroll through social media, my mind quickly rushed to the thought: "Wait, the guy who sang 'Can We Talk' is gay?".

At the latter end of a long career in the spotlight, Tevin Campbell has chosen to share his truth. Three years ago, the R&B icon opened up about his homosexuality, unravelling the truth that lay beneath the lyrics of his timeless hit tracks, which often suggested otherwise: "Can we talk, for a minute? Girl, I want to know your name…"

Tevin Campbell found his way to fame in early adolescence, signing his first deal at just twelve years old to none other than Quincy Jones' record label. I was personally introduced to Campbell through his 1991 guest appearance on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, where he played the crush of Ashley Banks—it was clear that his gifts were multi-layered.

His most famous song, "Can We Talk" was released in 1993 and catapulted the young talent into superstardom. Although Babyface wrote the track, it's compelling to think that Tevin was, in fact, thinking of a man when he sang it. However, no one would know this for another twenty years.

In the present day, Tevin Campbell has finally found solace in speaking openly about his sexuality. His actual "coming out" statement was relatively simple—in 2022, he tweeted, "Tevin is… [Pride flag emoji]" before quickly deleting it. In interviews since then, he has opened up about always knowing that he was gay, but when it came to his stardom, he reflects, "you just couldn't be [gay] back then."

Things changed in 2005, when he truly found himself whilst acting in a production of Hairspray. Surrounded by other queer creatives unashamedly being themselves, Tevin realised that things could be different—around him, he saw "LGBTQ+ people that were living normal lives with partners. I had never seen that."

In an entertainment industry and culture that historically shunned romantic ideals that didn't fit heteronormative standards, many celebrities (especially those who found fame in previous eras) have been conditioned to keep their homosexuality to themselves.

Perhaps it's none of our business, but then again, like everyone, these stars should always have been able to live in their truth and express themselves without fear of judgment. Exploring Tevin Campbell's journey made me think of other stars who had experienced a similar path.

Not all celebrities are allowed to share or withhold their sexuality on their own terms. Take George Michael, who was arrested in 1998 for "lewd conduct" after being caught by an undercover officer whilst engaging in a sexual act in a Los Angeles public toilet.

Of course, within minutes, it was a press story, and the world immediately knew something Michael had kept to himself for so long. Where some people would run and hide, George Michael held his head high, later declaring in a powerful CNN interview that, although he felt reckless for being exposed in his way, "I don't feel any shame whatsoever, and [nor] do I think I should."

Emboldened by his own truth, George Michael rewrote the narrative that had been stolen from him. His notorious track, "Outside" (released in the same year of his 1998 arrest) is an exhibitionist anthem—in an act of reclamation, he created an entire song about having sex outside, featuring audio from news reports about his debauchery.

In the unforgettable music video, scenes of both gay and straight couples performing romantic acts in public are interwoven with scenes of Michael and dancers partying in a men's public toilet turned into a disco. The final scene shows two police officers passionately kissing. This kind of bold, unapologetic resilience could only be born from someone tired of holding their true selves back, galvanised by being vilified for his identity and sexuality.

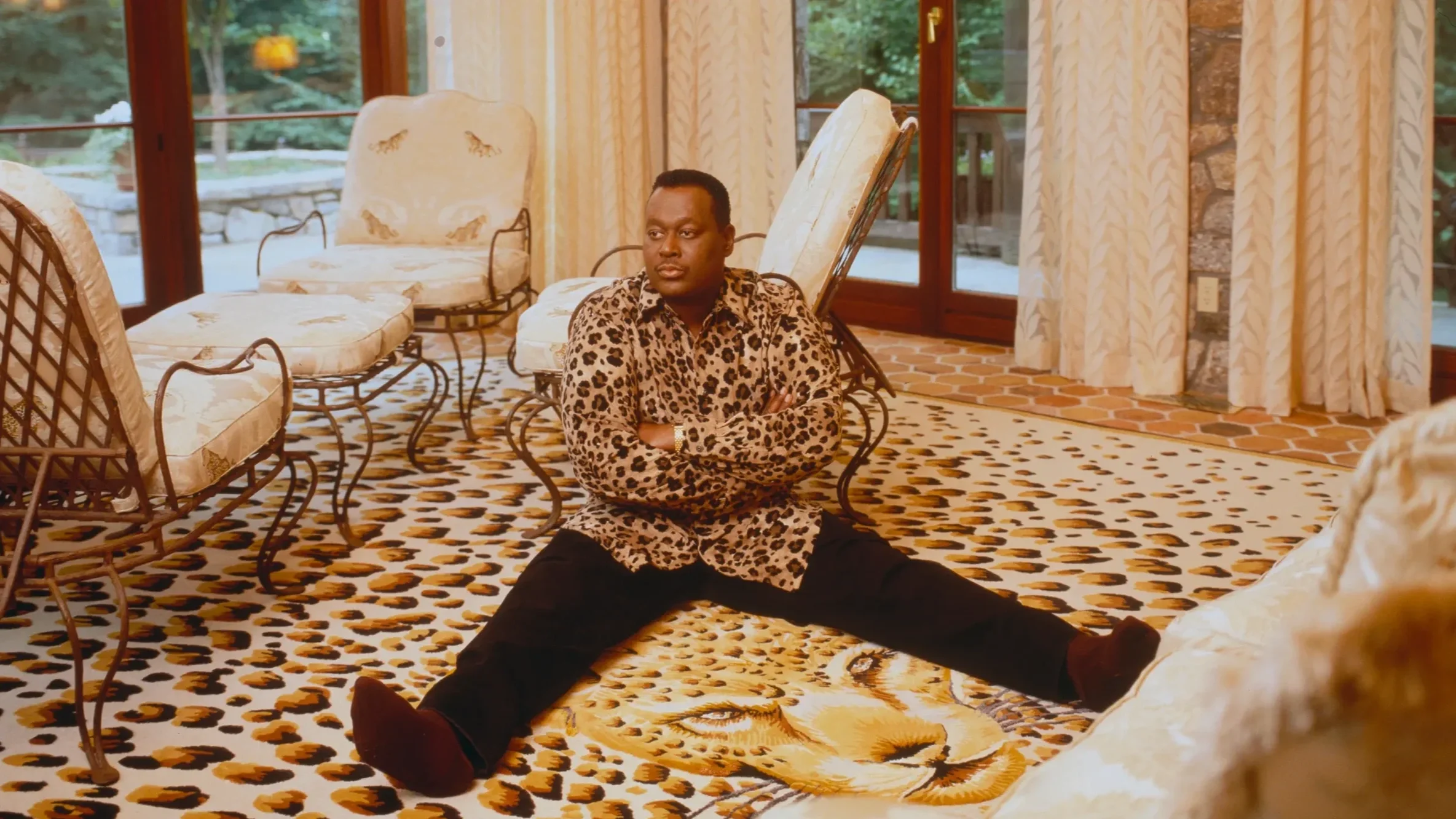

We can also turn our attention to singers who were more subtle about their homosexuality, keeping this part of their identity locked away for the entirety of their career. The inimitable Luther Vandross provides a fine example of this. Known and adored deeply for the timeless love songs that shone in his discography—from the uplifting euphoria of "Never Too Much" to the tender longing of my favourite song, "A House Is Not A Home"—the romantic subjects of Vandross' lyrics did not match the desires of his heart.

Some say that Luther Vandross' homosexuality was one of R&B's "best known secrets", but this was all speculation until 2017. On Andy Cohen's Watch What Happens Live talk show, twelve years after Luther's passing, his dear friend and fellow icon Patti LaBelle spoke about his identity as a gay man during her interview. Some accuse LaBelle of "outing" the star, who was notorious for keeping his love life to himself. Unfortunately, in this case, the discussion of his sexuality on a public platform was out of the late icon's hands.

Whether right or wrong, in speaking of her late friend's life, LaBelle cited several reasons why Luther never came out, including that "he had a lot of lady fans… he just didn't want to upset the world." This is a powerful sentiment when thinking about the lack of queer presence in R&B and popular music.

The minute these artists began singing about love, they were presented as a site of consumption for heteronormative society. If they were to sing from a queer perspective, they would no longer fit that criteria, so it was either sing straight or don't sing at all. George Michael commented that "for some reason", gay life didn't become easier after he came out.

In one of his last interviews, for People in 2014, he shared that, "The press seemed to take some delight that I previously had a 'straight audience,' and set about trying to destroy that. And I think some men were frustrated that their girlfriends wouldn't let go of the idea that George Michael just hadn't found the 'right girl'".

“Tevin Campbell, George Michael and Luther Vandross were heartthrobs in their respective eras, carrying the weight of their fans on their shoulders. You can imagine their fear of expressing their true same-sex desires and consequently ‘alienating’ the majority of their doting female audiences.”

In Revolutionary Acts: Love & Brotherhood in Black Gay Britain, Jason Okundaye comments that evaluating gay history is often a "rescue effort"–an excavation of critical moments that have been lost, but would otherwise have been held sacred if they were of heteronormative origin. In some cases, history has been actively erased.

Okundaye writes, "Living under a state which has historically deemed 'other' people's lives to be of little significance means that its institutions—whether archives, libraries, museums, universities or other projects that define the boundaries of historical existence—may deny them a space in public record, leaving them in danger of being forgotten."

I believe that to evaluate these careers through a queer lens, we have to approach it with a specific type of revisionism. These people are gay icons in their own right, even if they never had the chance to present as that, to experience that type of acceptance. Regardless, their contributions to queer culture are undeniable, and the only way to honour them is to recognise them as they truly were. They were gay artists and that shaped every lyric they sang.

Today, non-heteronormative R&B seems to feel unsheathed. Artists like Destin Conrad, kwn and Kehlani are becoming household names, with the latter recently reaching No. 1 on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs Chart with their track "Folded".

I mourn the songs we perhaps didn't get from artists gone by—the more specific, the more particular. Still, I celebrate every lyric we got to hear, every live performance we got to see, every outfit, every interaction: they are all the actions of queer people, and they should be seen as such. That's how we can complete the rescue effort.

Long live queer R&B.