BFI London Film Festival Standout 'Ackee and Saltfish' is a Must-Watch

In just 15 minutes, newly anointed writer-director Jasmin Nunes unravels a familial tale rooted in motherly perseverance, inner-city integration and cultural erosion.

It's hard to sell a short film without leaking too much of its narrative nectar, but Ackee and Saltfish is essential viewing. Big Apple filmmaker Jasmin Nunes directs and writes the short in her stellar film debut. They often tell new script writers to "write what they know", so Nunes does just that.

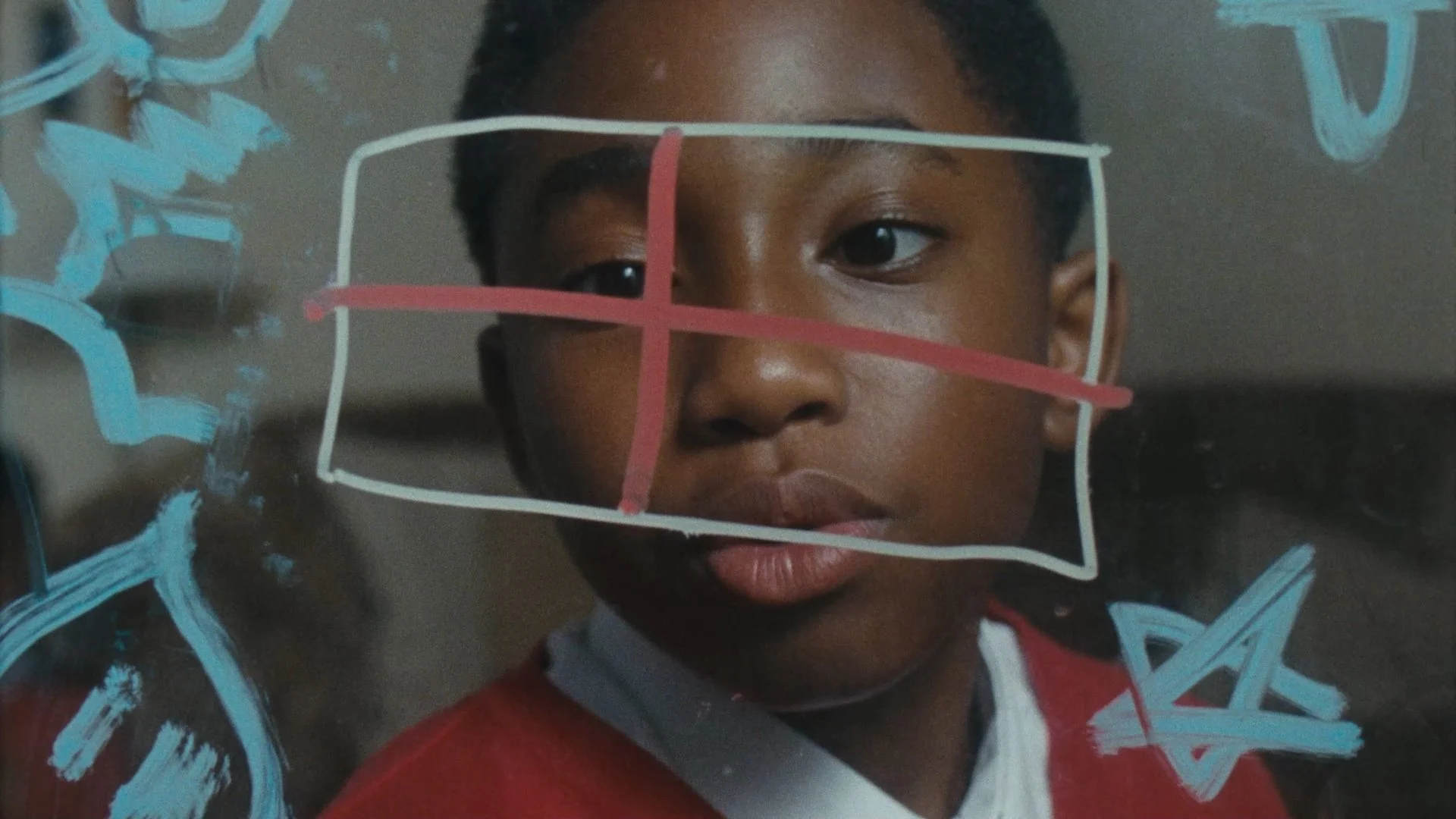

Yanking on the coattails of her short time in London's municipal sprawl, Nunes centres the film on three characters: Hilda, a mother (Simone Frazier) and her two young football fanatic sons. As Jamaican expats adjusting to life in the UK, the movie revels in audio-visual storytelling—letting the music, dynamic cooking ensembles and emotive performances lead the short.

But beneath its warmth, Ackee and Saltfish poses a quieter conversation. For Nunes, the film was always more than a snapshot of a household; it was a meditation on the smaller, less-dramatised realities of transformation. "This narrative is all about acculturation and what surrounds it," she tells The Culture Crypt.

Nunes wanted to amplify a truth often overshadowed by more catastrophic immigration stories—the ones dominated by displacement, loss or crisis. "I wanted it to speak loudly about something that wasn't as cataclysmic as the typical narratives you usually hear," says Nunes.

She adds: "This was an unheard story, an unseen story that I felt was universal to both Black Brits and myself as an African American. My goal here was to explore acculturation."

With no frightening third-act antagonist lurking in the shadows of a back alley, Ackee and Saltfish arguably positions the television (an allegory for cultural hegemony) as the closest thing to a moustache-twirling villian. Throughout, Hilda's boys morph into micro-geezers—as they absorb the cheer, colloquial lingo and cultural norms beaming out of their televsion.

Nunes is clear about what she hopes audiences take from Ackee and Saltfish. Like any filmmaker, she starts with intention, knowing that once a film leaves her hands, its impact is beyond her control. What she can shape, she tells us, are the emotional pockets she chooses to spotlight. "I wanted to illuminate that [narrative] dissonance," Nunes reveals, "to bring awareness to the quieter moments."

If you ask many, culture wars have intensified in 2025. For Black Brits, immigrants' livelihoods are threatened by lost social rights, widespread discrimination and rising xenophobic nationalism—just the tip of the social warfare at play. Regardless of the artistic intent, Ackee and Saltfish is being made in an era where positive, nuanced and authentic Black representation is in short supply.

“As a child, I didn’t see my face or anyone who looked like me on the screen. That lack of representation was huge. Not only do we deserve to exist, but we deserve to exist in media—widely. I think right now, we’re in the midst of a Black renaissance.”

For every BAFTA Award-winning David Jonsson or NAACP-nominated Jodie Turner-Smith, Nunes believes that silver screen stories with Black and minority casts are still frustratingly narrow and tokenised. She's determined to widen that frame—not by ignoring racial oppression, but by refusing to let it monopolise the 35mm conversation. "Racial oppression bleeds into our everyday lives, that's a given," declares Nunes. "But that shouldn't be the only representation we have in the media and on screens."

To us, Ackee and Saltfish is a quintessential watch. Not because it's life-changing, but because it's a quiet, thought-provoking reminder of how human Black stories can be on screen—slave-driven dramas be dammed.

Learn more about Ackee and Saltfish on the BFI website here.